Links and Resources

This is an edited version of the website that the citizens’ assembly used during the process. All the videos that contain identifiable information has been removed, in accordance to the requirements of the UAHPEC.

Questions

Education and behaviour

Q: What education programmes are there for more intelligent usage? (be conscious of flow from tap, save a flush, pee in the shower)

A: Watercare has an education programme with schools. They are developing a water literacy strategy and use communication channels to spread useful messages to reduce water wastage. Haven’t seen a pee in the shower campaign yet!

Q: How can we educate the population to accept recycled water?

A: If the assembly did go for a wastewater recycling option Watercare would need to work with Aucklanders to improve understanding of this option, particularly around safety, drought, and the benefits to the environment and energy use.

Q: Are commercial users incentivised to reduce water consumption?

A: They are incentivised insofar as they get lower bills and Watercare provides a water audit service (free) that can advise them how to reduce their water usage.

Environmental considerations

Q: With Climate change now being obvious, shouldn’t the 30 year plan include 100 years?

A: We don’t know what will happen in 100 years but when we plan for a thirty year horizon, we still expect our assets to last well beyond that (like our dams)

Q: Can we get some more background about the environmental impacts of desalination discharge? What studies/data do we have on local environmental impact and global environmental impact?

A: The environmental impacts are the return of the brine into the environment (which can have an impact on marine life) This is still being studied.

A: can have an impact on marine life) This is still being studied.

In the Arabian gulf, ecologists have noticed changes in species composition and shifting of spawning seasons near a desalination plant. The cumulative long-term effect on receiving water bodies and their biodiversity is unclear.

Q: Have RMA/NZ coastal policy laws/AEE been considered?

A: Whichever option(s) we go with, we will need to meet increasingly strict environmental standards (RMA).

Wastewater and environmental impacts

Q. What is the exact process of removing waste from wastewater and where do they go? Can we ensure that the waste from the recycled water is disposed of in an environmentally friendly way?

A: The stuff that is more than 3mm thick is captured in filters and trucked to landfill.

A: The residual sludge is dried and currently used as beneficially as possible, with increasing benefits as technology allows.

Q: What are the environmental effects of by-products on the Manukau harbour? Are there any studies of environmental changes occurring in its vicinity?

A: Levels of some contaminants (e.g. copper, lead and zinc) were elevated in the Māngere Inlet, possibly as a result of wastewater discharge. The disturbance to ecosystems has lessened with improvements to wastewater treatment facility, according to a recent environmental monitoring report (https://www.knowledgeauckland.org.nz/media/2120/synthesis-state-of-the-environment-monitoring-manukau-harbour-final_web.pdf). Recycling water would further reduce impacts on the harbour as less treated water would be released.

Q: Relatively speaking, how much waste is produced by each option (recycling and desal), and what is the relative yield of drinkable water?

A: For wastewater recycling, the amount of solid waste is the same as it is now, it’s just the waste from our wastewater treatment. With recycling options, we would be using the water instead of putting it into the harbour after treatment.

A: With desalination, the waste is brine that must be discharged in the harbour. The yield of drinkable water from the amount treated is lower than with recycling.

Q: What happens to the waste products of the recycling options?

A: There is an opportunity to capture nutrients for re-use with recycled wastewater. It is likely that there will always be some waste product that will need to be put into the environment just as we do today with wastewater by-products.

Q: For the sludge by-products of option 3, how much is discharged to landfill compared to current wastewater treatment practice?

A: The amount of solid waste is the same – the water portion that is being purified and re-used

Cultural considerations

Q: Direct - option 3: Have you considered the mauri of the water?

A: The mauri (life force) of water is an important consideration and often part of the statutory approvals process eg. under the Resource Management Act

A: We would need to develop any option in partnership with mana whenua and can use some established principles to help us

A: We will need to work through this during session three as we prepare a draft recommendation for mana whenua to review.

Working with mana whenua

-

- Watercare works closely with Mana Whenua through the Mana Whenua Kaitiaki Forum which you can read about here: https://www.watercare.co.nz/

About-us/Who-we-are/Mana- whenua. This relationship is ongoing. Part of the reason Watercare wants to start talking about our next water source 20 years in advance is that we have learned from mana whenua to engage early.

- Watercare works closely with Mana Whenua through the Mana Whenua Kaitiaki Forum which you can read about here: https://www.watercare.co.nz/

-

- The assembly will be able to talk more about the views and relationship with mana whenua kanohi-ki-te-kanohi (face-to-face) on Saturday. University lecturers and hired experts are unable to answer these questions on behalf of tangata whenua and it was felt that a face to face meeting was more appropriate for this.

-

- Tame who heads the mana whenua kaitiaki forum has agreed that the mana whenua kaitiaki forum will review the draft set of recommendations after day three and provide questions and feedback by the 24th of September.

-

- What happens to the waste by-products from wastewater is well illustrated in this video: https://www.watercare.co.nz/

Water-and-wastewater/ Wastewater-collection-and- treatment which is already up on the website. The disposal of brine would be out at sea unless better technology came along OR our citizens insisted that we do something else with it. Rob from Watercare’s resource recovery group will bring in some new fertiliser products on Saturday for anyone who is interested in beneficial recycled products of our waste.

- What happens to the waste by-products from wastewater is well illustrated in this video: https://www.watercare.co.nz/

Costs (energy or $)

Q: Please explain energy costs vs ongoing costs

A: They’re largely the same thing. Ongoing/running costs mainly come from energy use, so there is also an emissions ‘cost’ to this.

A: Innovation increasingly helps water companies operate more sustainably/efficiently. Maintenance is also an ongoing cost.

Q: How much do rain tanks cost? (Plumbing, maintenance, etc ). Is this a cost effective option a resident/individual?

A: It depends on whether the tank is plumbed in, and how big it is. If it’s small, it’s cheaper, but also less useful in summer. If well maintained, rain tanks can last up to 20 years.

A: As a large-scale option, costs are high for rain tanks because so many are needed in total to get relatively less water. (compared to large infrastructure options that we all share the cost of in our water bill).

Q: How long do rain tanks last?

A: This will be a function of the quality of the tank itself, the environment it’s used in (submerged in soil, above ground etc) and maintenance etc. Many polyethylene rain tanks have a 20-25yr warranty.

Q: Why is the water efficiency option costly?

A: Water efficiency includes some big costs like renewing pipes (digging up streets, traffic management, resealing the road), installing smart meters, campaigns for behaviour change, greywater systems (need to involve plumbers).

Q: What is the cost of recycling not-for drinking options?

A: The actual cost would depend on the scale of the solution. It would be higher than one large infrastructure option because we would not get the economies of scale from many micro-solutions. If it were a larger option, it would require a second network of pipes.

Q: What about cost of desalination – will it make water more expensive?

A: Desalination is about the same cost to build as option 5 (indirect recycled water for drinking) but more expensive to maintain.

Questions about funding

Q: Where is the money coming from to fund these options? What is the cost to the public?

A: Money only comes from bill payers. The cost to the public is the cost of building and operating these options spread over the whole population of bill payers.

Q: Are there plans to subsidise rain tanks in the future and their maintenance requirements?

A: There are no plans in place for this. If it happened, it would be paid for by Auckland billpayers (a redistribution of income, likely to be from people without gardens to people with gardens)

Safety considerations

Q: Can direct recycled water (option 3) be treated to a level where it is safe to consume?

A: Yes. technology exists to do this now and it is often used in large international cities.

Q: Are there contaminants that can’t be tested for yet?

A: There is a lot of focus in the water treatment industry on new classes and groups of contaminants, and analytical methods are continuously improving to detect them.

A: Biomonitoring provides additional assurance that untested or not yet detected chemicals of concern would not go undetected.

A: When processing water from a wastewater treatment plant, they will use reverse osmosis. This process removes everything out of the water, even dissolved salts. This combined with the multiple barriers will cover these contaminants.

Q: What sort of ‘natural filtration’ occurs in the environmental buffer? What additional benefits does this provide?

A: This will depend on the type of buffer that is used. The water going into the buffer is first treated to a very high standard, but can sometimes become contaminated in the reservoir/buffer. It is therefore re-treated before being pumped into the drinking water distribution system.

A: A point about safety is that indirect recycled water can be higher risk than direct. It is important to note that some systems which indirectly treat recycled water – like downstream of discharges – are not as safe as direct recycled water schemes that have been actually designed to minimise the risk.

Q: Are there studies on existing direct/indirect purified water systems and their environmental or health/living impact on residents compared to neighbouring residents that don't use it? How long have these recycled water systems existed for these studies?

A: There is no evidence that consumption of purified recycled water systems causes any adverse health effects. The impact on the environment is expected to be beneficial, because treated wastewater is not discharged to the environment. (*see question about Namibia)

Q: In Namibia, has there been long term monitoring of effects of water use?

A: Namibia’s recycling system has been running since 1968. Over the many decades since then, the consumption of drinking water from the Windhoek system has not been directly associated with any adverse human health impacts.

A: Austrian commentators studying Windhoek’s scheme have noted that –

“…the people of Windhoek have even derived some pride from the fact that they are the only ones where direct potable reuse is applied worldwide. A prerequisite for this success was of course that since the beginning of potable reuse in 1968 no outbreak of waterborne disease has been experienced and no negative health effects have been attributed to the use of reclaimed water.” From Water Management in Windhoek/Namibia

Q: Can the water treatment plant become overwhelmed and less efficient or nonfunctional due to high amount of pollution, sudden or constantly increasing?

A: The processes that are already in place would be expected to pick these up and treat correctly (In the case of a sudden pollution E.G. Meth lab dumped).

A: Plants are built to handle peaks. If it gets progressively worse, the plant slows down to ensure quality. At worst, a plant will be closed to problem solve. Large utilities proactively monitor and have predictive models to reduce fear of worst case scenarios.

Q: What minerals will be in our drinking water as a result of wastewater recycling processes? Do the treatment processes remove beneficial as well as harmful minerals?

A: Desalination and water recycling remove everything from water even though it may have been beneficial (e.g. some minerals such as iodine). This water needs to be re-mineralised in the treatment process.

Q: Is there a buffer if something goes wrong?

A: Public health is critical and the treatment systems are very closely monitored before water enters the piped network.

A: These systems have a range of safeguards and a high ‘margin of safety’, meaning that they are designed to deal with occasional breaches of contaminant levels and keep the water safe for drinking.

Q: Can we see water quality analysis for desalinated and recycled water so we can compare the remaining impurities after treatment such as pharmaceutical contamination and treatment byproducts?

A: The treatment systems use membranes that remove all contamination products from the water.

A: If referring to the solid waste stream – for recycling this is the same as for wastewater treatment we use now. There are ways to make use of solid waste, such as in fertilisers and biofuels

A: The waste stream from desalination is mainly concentrated brine (it is taken from the sea, and put back into the sea in more concentrated form).

Questions about options

Recycled water for drinking

Q: Has the quality of recycled water been proven over many generations (long-term analysis)?

A: Direct Potable Reuse has been in operation in Windhoek, Namibia for more than half a century (since 1968).

A: Since the 1980s, thousands of water reuse projects have been developed around the world, and it is estimated that more than 200 water-recycling schemes are in operation in the European Union.

A: Many states in the USA use direct recycled water

Q: Some people may not accept the purified recycled water from sewage, but can accept that from stormwater. Can these two resources of wastewater be treated separately?

A: Stormwater and wastewater are different and are already treated separately – they have different pipe systems underground. It’s important to understand that stormwater might look cleaner than wastewater but is actually quite dirty. Water from roofs is more likely to be safer and cleaner than water that has run over the roads.

Q: I've read that there are higher nitrogen and phosphorus levels in purified recycled water? Is this true? Isn’t it also the case that some minerals have to be added to Advanced Treated water, because those plants remove all things non H2O?

A: Advanced water treatment (including desalination) remove all minerals from water, so some that are important to receive via the water supply need to be added back at the end.

Q: A far as I understand, conventional prion detecting methods don't work very well in water so would we have to hope that nanofilters in waste-treatment are able to efficiently remove prions?

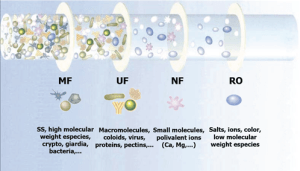

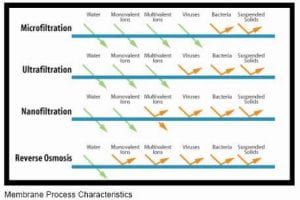

A: Prions can be removed by effective filtration and reverse osmosis. Treating wastewater or seawater to a drinkable standard would require both filtration and reverse osmosis in the advanced water treatment plant.

UF Purification versus Microfiltration, Which Process To Choose For Your Application?

https://www.safewater.org/fact-sheets-1/2017/1/23/ultrafiltrationnanoandro

Q: If direct recycling is cost effective then why efforts are not made to create more awareness among people to accept this method?

A: The issue seems to be a political one rather than a scientific one. The Water Services Association of Australia has produced this document about the growing acceptance of recycled water options which might be useful:

https://www.wsaa.asn.au/publication/all-options-table-lessons-journeys-others

Q: Does the water taste any different - can one identify which water is recycled or which is not?

A: You cannot tell the difference because the water from all water treatment plants is ‘pH balanced’ to make it safe and taste good.

Q: Will indirect and direct treatment plants be turned off when the storage is full?

A: This can be done but it is better to plan for the amount of water needed rather than turning systems on and off. The recycled water systems can continue to be used when dams are full, rather than drawing from them, leaving that water storage for times when demand is higher or there is a drought.

Q: Which method needs to be run less and can save cost?

A: Direct treatment for drinking is cheaper to run, because although they make the same water, it takes money to pump around the recycled water into water courses/dams etc.

Differences between the recycled water options

Q: What are the key differences between options 3, 4, and 5?

A: Direct (option 3) = wastewater goes into an advanced water treatment plant and is then pumped into supply

A: Indirect (option 5) = wastewater goes into an advanced wastewater treatment plant then into a lake, river or groundwater storage, then into advanced water treatment, and is then put into supply

A: Water in option 4 is not for drinking. It would be conveyed in different pipes and must be kept separate from drinking water networks.

A: Drinking water must meet very strict guidelines before it is put into supply. These guidelines ensure that the water is safe to drink.

Q: Can we get option 3 in enough scale for both options – drinking and not drinking? Then we wouldn’t need option 4.

A: Yes – option three at 150 MLD would be enough for drinking and non-drinking. Also note that there are strict quality standards that need to be met whether for drinking or other use (ie. you have to treat wastewater well before you put it into the environment anyway)

Q: If option 5 is more expensive, why is it more common? Is it just a cultural thing or are there other reasons for not using option 3? Why is the carbon cost to build this option so much higher than option three?

A: There are some storage (resilience) benefits of indirect recycling (option 5). With this option, a reservoir (storage) would need to be built.

A: Option 3 doesn’t require a reservoir to be built. With the Rosedale option previously identified, the treated water would need to be pumped uphill to the built storage lake so there is an additional energy requirement to operate that option.

Recycled water vs Desalination

Q: How would a desalination system compare to waste treatment? (cost, efficiency, purity)

A: Cost: wastewater treatment costs less than desalination

A: Efficiency: waste treatment is a lot more efficient, with higher water volume recovery. Reverse Osmosis is required for both but there is less pressure on the treatment plant for wastewater treatment, because you have to process so much more water with desalination to get the same amount in the end (yield)

A: Purity: Risks are a bit higher with waste treatment because seawater has lower concentration of contaminants.

Q: What about evaporation systems in waste treatment?

A: Evaporation systems can be used to reduce the water portion of water-based wastes by converting the water portion to water vapour. This does not contribute to water supply but could reduce the volume of treated water being released to harbours/waterways.

A: Evaporation technologies are sometimes used to treat the waste stream from desalination, thereby recovering salts and other minerals, and reducing/eliminating the discharge of brine, but these processes are currently very expensive. Evaporation ponds are most efficient in the arid or semi-arid areas (that means, not Auckland!).

Desalination technology

Q: Is this the only option for desalination? Is there anything that is more efficient/sustainable?

A: The methods presented represent what is currently possible/practical. The limits of what we might do by 2040 are not known. Nothing is set in stone and nothing has been decided.

A: This is a constant area of research internationally as desalination becomes more widespread as a source of water. If chosen as a way forward, significant investment would be made on how to do this well – protecting people and the environment and improving efficiency.

Q: Has anyone approached the Navy for information as they have experience of desalination on ships. Could we run a pilot programme?

A: We have asked the Navy – this may be classified information. We are making enquiries and will come back to you.

Location of facilities, and where the water goes

Q: Where would the treatment plants go, and who gets the water? Has the site already been decided or is this still up for discussion? (for all potential sources)

A: Nothing has been decided yet – the option would have an impact on the site, and this is what the assembly is for

Q: Are poorer communities or certain areas going to receive more direct purified water than others if we don't mix it in a reservoir? Will there be a mix of water sources to those areas?

A: Recycled:

If the recycled water source is in the North, there may not be enough volume to shift it south. The shore will still end up with a blend. In Summer it will have more water coming in from the south to blend, while in winter it would provide the majority of the shore water.

For Mangere it will depend on how it’s configured.

A: Desalination:

No particular site has been specified yet. It could be either in the Hauraki Gulf (easier to manage) or out on the West Coast (better for mixing but harder to manage)

If Hauraki it would likely be Rosedale (where our wastewater assets are)

Q: Option 4: How much of this would be used for residential vs. commercial use?

A: Non-potable use would be for organisations and businesses who have need for lower quality water. It is not practical to construct the pipe network necessary to provide non-potable water for general residential use.

Rain tanks

Q: How would we go about implementing rain water tanks if this option were chosen?

A: Even if it were mandated the cost and responsibility of installing rain tanks would be borne by the household. If this were subsidised, the cost of subsidisation would be paid for by the billpayer. The water utility would still need to have capacity to supply the household during dry spells unless the mandated tank size was 2×25,000 litres. Therefore, we still would need another source until everyone had two large rain tanks or are prepared to go without water during a drought. This is why this option is so expensive.

Q: Yield – rain tanks: Does the 10-15% saving from water tanks represent the current number of tanks? Or does it relate to if everyone had a tank?

A: It is 15 million litres. This is the possibility for 1/3 of Auckland roof space having tanks attached.

Q: Why didn’t we make it compulsory to have rain tanks plumbed to toilets?

A: Building regulations are set at the national level. Watercare encourages customers to have rain tanks but we know that plumbing them into the house is expensive.

Q: Rain tanks: does it matter how old the house is?

A: Age of house is not critical but it is easier to plan for and install tanks during building. Retrofitting to older homes can be expensive.

A: A few things would be required to make this work:

– Space for tanks

– Metro supply during droughts

– Backflow prevention

Q: Why can’t rain tanks be plumbed into the toilets?

A: They can be. This is done in some new developments. However, when the rain tank is empty, toilet flushing water must come from the metropolitan supply. It’s also more expensive than the larger source options (per household) and the cost will be borne by the household, not the water provider.

Q: In the early 60s, there were water tanks, the water in them we used for drinking, washing, cooking. We had no pumps for the tanks. Why is it different now?

A: It isn’t different, it’s about how reliable they are in summer and how densely packed our city is. In summer you need space for 2x 25,000 litre tanks to be self-sufficient.

General Questions

More storage, please

Q: Can we save water when we have high rainfall to use later? In the years we have high rainfall can we not store it to use when we need it – both for rain tanks and dams?

A: This already happens with storage reservoirs. However, in very dry years the storage can be insufficient. Smaller rain tanks cannot store enough water for long periods of drought.

Q: Why not simply build more storage for rainwater from overflowing dams? Maybe build a dam/lake which will be filled in high rainfall times and stored for when there is less rain? Wouldn’t this reduce the need for expensive treatment and infrastructure? How much storage is needed, and is there an available site? Will there be enough rain to fill it?

A: Environmental and space issues make it challenging to construct more storage. We wouldn’t be able to build enough storage to make a single source for the future.

A: Different sites/options have been assessed. Environmental protections stop us from building in many places. A site near Rosedale wastewater treatment plant has been considered and this would be Watercare’s second largest dam. However, the streams to fill it are very small, and there would need to be recycled water to fill it (this would be indirect recycled water).

Q: Will a new source be the primary source or just a top-up? Will dams still play the main role as a source?

A: The dams currently supply about 70% of Auckland’s water. This reduces in a dry year as we rely more on the Waikato River. Over time, other sources will become more important. They will supplement the dams.

Auckland Council’s Water Strategy

Q: Are the water strategy’s targets conservative or ambitious?

A: The targets are the result of joint council and watercare work. We modelled a plausible maximum water efficiency and a ‘no change’ scenario giving us a scope of opportunity for change. The targets ended up being right in the middle of this scope of opportunity. They represent conservative assumptions about background (‘natural’) water efficiency improvements (such as appliances) as well as conservative estimates for behaviour change etc. One thing to note is council and watercare staff were instructed to return to council’s elected member committee in 2024 with more ambitious targets – i.e. there is room for more aggressive investment to deliver more and faster consumption reduction across residential, commercial and leakage.

Q: How difficult is it to integrate water strategy into regulation such as the building code?

A: Not many water strategy actions require changes to the building code. Some do, for instance the ‘plumbing in’ of detention tanks to the dwelling for use in the dwelling (such as for a toilet). This is challenging as the central government manages the building act. This means council’s lever is one of advocacy. Council is progressing this line of advocacy.

Planning for the future

Q: You mentioned we have had a good winter season – does that mean are we not worried for drought during this year's summer?

A: When the dams are full in winter, we don’t worry so much about the following summer. In 2019 we began to worry about the following summer because our dams were at around 69% full and the two summers coming were projected to be dry

Q: I didn’t understand Jon Reed’s chart showing droughts towards the end of the chart but having dated years all over the x axis, not in date order

A: The chart showed years in order of decreasing water supply (from rain). The years at the right (in red) are the drought years, several of which have been recent. This was to show that what we need to plan for is the years where we don’t have enough rain, which are becoming more frequent.

Q: Have any studies been done on city populations levelling out after rapid population growth? Do we know that Auckland will grow exponentially (and therefore we do require another water source within the next 5-10 years)?

A: Cities around the world are growing, and more people are moving to urban centres than out of them. We may hope that population growth slows or declines but we must plan for growth.

Fact checking

Q: Can we ensure rules and regulations are in place to stop companies bottling and selling our water first and foremost?

A: There is a prevailing idea that NZ is selling a lot of water overseas, but it is not borne out by facts. A Stats NZ report on the volume of bottled water exported for 2019 (pre covid) was ~110,000m3 for the full year, over the entire country. That equals a quarter of one day of Auckland’s water use.

A: Water is used by businesses in Auckland for food and beverage manufacturing. Some of these products are sold overseas.

Q: How much of the network still uses asbestos plumbing? How much of a risk to health is this?

A: There is asbestos pipe from 60 years ago, exact figure we don’t know.